This topic explains why mental confusion and stomach discomfort can appear at the same time. In clinical terms, brain fog nausea describes a pattern where thinking feels less clear while nausea is also present. There is no single cause that explains every case. These symptoms may be related to changes in brain signaling, hormone levels, sleep quality, or the stress response. They often come and go, which can make them hard to understand.

This article is written as a clear medical explainer. It focuses on how brain symptoms and physical symptoms can overlap. SensIQ is mentioned only as an educational platform that helps explain how brain processes affect daily life. The purpose is to inform, not to diagnose or treat.

Key Takeaways

- Brain fog and nausea often appear together because the brain and digestive system share signaling pathways that regulate balance, hormones, and stress response.

- These symptoms can arise from several overlapping factors, including poor sleep, hormonal changes, dehydration, and physical or emotional stress.

- Temporary episodes are common, but a qualified clinician should evaluate persistent or worsening symptoms to rule out underlying health conditions.

- Tracking patterns such as sleep, diet, and stress exposure can help identify possible triggers and improve communication during medical visits.

- Research suggests that brain fog and nausea involve the nervous and hormonal systems, highlighting the need for individualized assessment rather than one universal cause.

What causes brain fog and nausea?

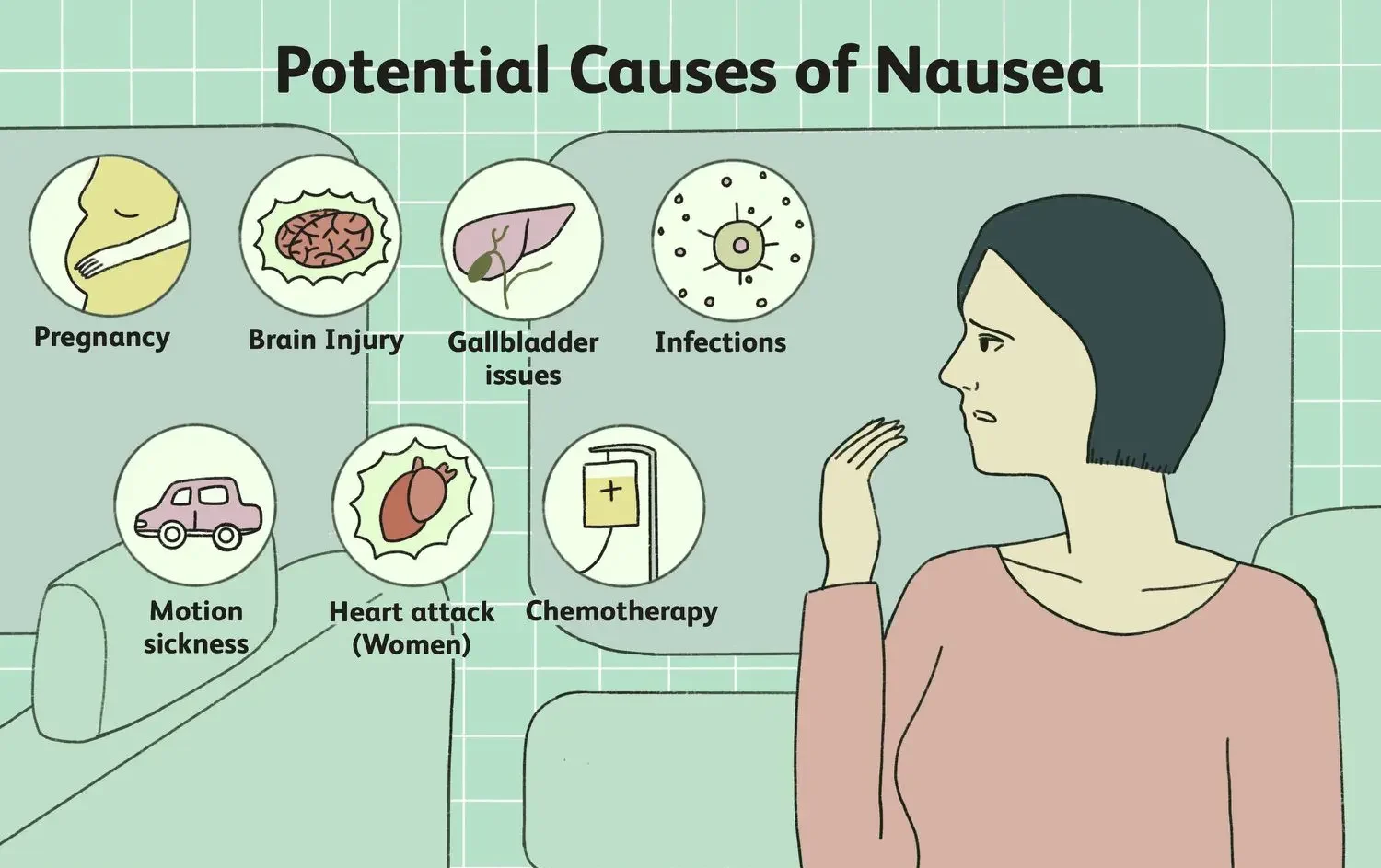

Mental fog and nausea can stem from multiple factors, including those often linked to the causes of brain fog. Often, they reflect short-term changes in how the brain communicates with the rest of the body. The brain sends signals that help control balance, digestion, and alertness. When those signals shift, symptoms may appear.

Common triggers include poor sleep, long-lasting stress, hormone changes, and physical exhaustion. Dehydration, irregular meals, or long gaps between eating can also play a role. Recovery from illness or ongoing inflammation may also contribute. In some cases, symptoms develop from a combination of smaller factors rather than a single clear cause¹.

Doctors also look for underlying health conditions that may affect energy or thinking, including factors such as high blood pressure and brain fog. These can include infections, changes in blood sugar, thyroid imbalance, or nutrient deficiencies. Medical evaluation focuses on patterns over days or weeks, not just on a single episode. The whole context helps guide the next steps.

Common day-to-day triggers

Some triggers are linked to simple routines. Extended periods at a screen without breaks can strain the eyes and mind. Skipping breakfast or eating very late can unsettle digestion. Caffeine, alcohol, or large meals late at night may also make symptoms more likely the next day.

Noticing how symptoms change after these routine events can be helpful. Keeping track helps separate rare one-off episodes from repeat patterns. Minor adjustments, such as regular meals and short breaks, may ease the system’s workload. These changes do not replace medical care, but they can support basic regulation.

When causes are less clear

Sometimes the cause of these symptoms is not apparent. Laboratory tests may look normal, and scans may not show a clear problem. In these cases, clinicians often look at stress levels, sleep quality, and overall workload. They may also review medications and recent illnesses.

Lack of a single clear cause can feel frustrating. It does not mean the symptoms are imagined. It often implies that regulation is complex and involves several overlapping factors. A stepwise approach over time can be more helpful than expecting a straightforward answer.

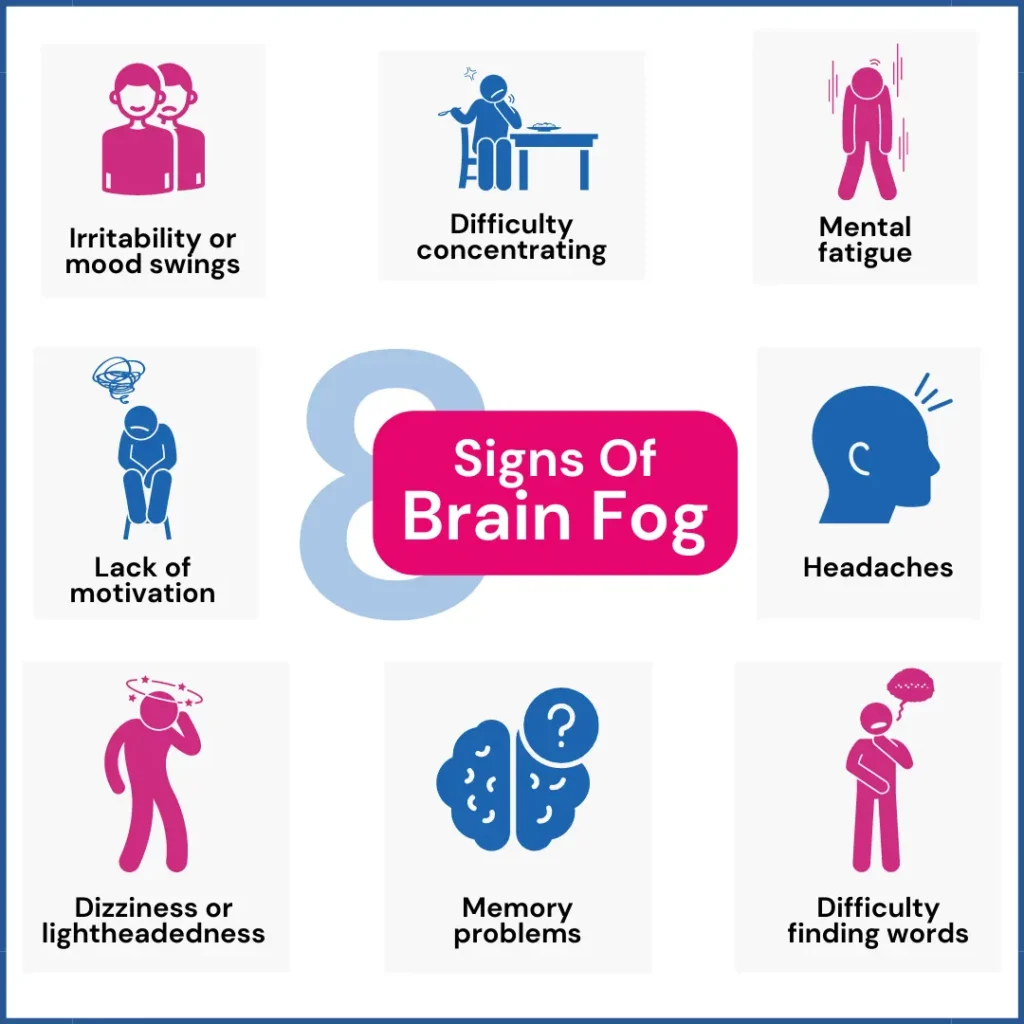

What brain fog is and how it feels

This term describes changes in mental clarity rather than a defined medical condition. Symptoms often include slower thinking, reduced focus, or difficulty recalling simple words. Mental fatigue may persist even after adequate sleep.

Symptoms can fluctuate throughout the day. Focus may decline after long meetings or extended screen use. Noise and multitasking can make thinking harder. These patterns are worth noting and sharing with a clinician.

These symptoms do not point to permanent brain damage. They usually reflect how the brain responds to overload, stress, or limited recovery. Recognizing this context helps reduce unnecessary worry or self-blame.

Examples from daily life

In daily life, brain fog may show up in small but noticeable ways. Someone might walk into a room and forget why they went there. Reading the same paragraph several times without absorbing it is another common report. Simple tasks, such as making a shopping list, may feel slower than usual.

These moments can be annoying and worrying. Still, they often point to strain rather than a severe disorder on their own. When these signs appear, they are usually worth mentioning during a medical visit. Concrete examples help the clinician understand the extent of impairment in daily function.

Nausea and brain fog: why they appear together

The brain and the gut are closely connected. They share nerves, hormones, and chemical signals. Because of this, nausea and brain fog often appear together. When regulation is disrupted, both systems may respond simultaneously.

The nervous system helps control digestion, balance, heart rate, and alertness. When it is under strain, symptoms can appear in different body systems. This can include mental clouding and stomach discomfort.

The autonomic nervous system manages automatic functions such as digestion and blood pressure². When its balance shifts, lightheadedness, nausea, and reduced mental clarity can occur simultaneously. This pattern is common and often improves with rest. .

Autonomic nervous system basics

The autonomic nervous system has two main branches. One activates the body for action, and the other supports rest and digestion. In a stable state, these branches balance each other. When stress is high or recovery is low, the balance can tilt.

This tilt can change heart rate, breathing, and gut movement. The body may send signals that feel like internal “noise,” such as stomach fluttering or chest tightness. These signals can be distracting and may feed into feelings of mental fog. Understanding this mechanism helps explain why symptoms often occur in groups.

Associated symptoms: dizziness, fatigue, and headache

Brain fog and nausea often appear alongside other symptoms. These can include dizziness, profound fatigue, or headaches. Some people feel weak or unsteady. Weakness, unsteadiness, pressure behind the eyes, or light sensitivity may also occur.

Fatigue can affect both the mind and the body. It may lower focus, reaction time, and stamina. Headaches may relate to tension, dehydration, or poor posture. Dizziness can increase worry, which may worsen symptoms.

Similar symptom patterns are seen in chronic fatigue syndrome, where energy use and brain signaling are altered³. This does not mean everyone with these symptoms has that condition. The comparison helps explain how symptoms can cluster.

How symptom clusters affect routines

When several symptoms appear together, daily routines can feel more complicated to manage. Tasks like driving, working at a computer, or caring for family may require more effort. Pace may slow, and busy environments can feel harder to tolerate. Over time, these changes can affect mood and confidence.

Identifying which activities feel most challenging can support practical adjustments. Short rest breaks, hydration, and pacing may ease daily demands. These steps are supportive, not curative, but they can reduce strain while medical evaluation is ongoing.

Digestive changes and loss of appetite

Nausea may reduce appetite or cause mild stomach discomfort. Early fullness or reduced food interest may occur. These changes reflect how digestion responds to brain signals and stress.

Short-term changes in appetite are common and often temporary. Still, eating less can lower energy and worsen fatigue. Small, regular meals and fluids help stabilize symptoms.

Digestive rhythm can also shift with sleep loss or hormone changes. The nervous system controls much of this process. Symptoms often improve over time, but persistent changes should be discussed with a clinician.

Hormonal factors, sleep, and stress

Hormones affect how the brain works and how the body feels. Changes in hormone levels can affect focus, body temperature, and digestion⁴. These changes occur across different life stages.

Sleep is critical for brain recovery. Poor sleep affects memory, mood, and attention. Stress adds strain by keeping the body in a constant state of alert, which is why stress-related topics like ashwagandha and brain fog are often discussed in educational settings.

When sleep loss, stress, and hormonal changes combine, symptoms may feel more pronounced. These factors often interact rather than act alone. This explains why symptoms may flare during busy or stressful times.

Why are these symptoms often misinterpreted?

Brain fog and nausea are often blamed on stress alone. This can delay proper evaluation. Symptoms may also change from day to day, which makes patterns harder to see.

Describing these sensations can be difficult. General statements like feeling “off” or “not themselves” often lack detail. This gap can lead to confusion or frustration during clinical discussions.

Clinicians recognize this challenge. Standard tests may look normal. Careful history and symptom tracking become key tools.

How to track patterns over time

Tracking symptoms does not need to be complex. A simple notebook or phone note can record when symptoms start, how long they last, and what was happening before. Sleep, meals, stress events, and activity levels are useful details to include. Over several weeks, patterns may become clearer.

This record can be invaluable in a medical visit. It provides the clinician with concrete data rather than general impressions. It can also reassure the person that their experience is real and consistent. Tracking is a tool to support, not replace, professional care.

When to seek medical evaluation

Medical evaluation is essential if symptoms last, worsen, or interfere with daily life. A clinician can help rule out health conditions that need care. Evaluation can also identify sleep, stress, or lifestyle factors.

Dr. Luke Barr, Chief Medical Officer at SensIQ, has noted in clinical education that cognitive and physical symptoms should be reviewed together. Looking at one without the other may miss valuable information. Professional guidance helps clarify next steps.

Questions to discuss with your clinician

Preparing a few questions can make a visit more productive. Examples include asking which possible causes fit the symptom pattern, which tests are reasonable, and which signs should prompt urgent care. It also helps to ask how sleep, stress, or hormones might be involved in the case.

Bringing notes about medications, supplements, and past illnesses is useful. Sharing specific examples of how symptoms affect work, family life, or driving gives essential context. This information helps shape a plan that fits the person’s real life, not just their test results.

What current clinical evidence shows

Research suggests that brain fog and nausea may share regulation pathways in the brain and hormones. Studies show associations, not guarantees. People respond differently based on health and environment.

Evidence supports an individual approach. Understanding mechanisms helps place symptoms in context. Research continues to explore these links. Clear information supports informed care.*

References

- Cleveland Clinic. (2024). Brain fog. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/brain-fog

- National Institutes of Health. (2018). Gut communicates directly with brain. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/gut-communicates-directly-brain

- National Institutes of Health. (2025). About ME/CFS. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/advancing-mecfs-research/about-mecfs

- Santoro, N., & Randolph, J. F., Jr. (2011). Reproductive hormones and the menopause transition. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 38(3), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2011.05.004

*These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.